Chapter 2 Formulating a hypothesis

“There is no single best way to develop a research idea.” (Pischke 2012)

2.1 How do you develop a research question and formulate a hypothesis?

You decide to undertake a scientific project. Where do you start? First, you need to find a research question that interests you and formulate a hypothesis. We will introduce some key terminology, steps you can take, and examples how to develop research questions. Note that .

What if someone assigns a topic to me? For students attending undergraduate and graduate courses that often pick topics from a list, all of these steps are equally important and necessary. You still need to formulate a research question and a hypothesis. And it is important to clarify the relevance of your topic for yourself.

When thinking about a research question, you need to identify a topic that is [based on [find source]]

- Relevant, important in the world and interesting to you as a researcher: Does working on the topic excites you? You will spend many hours thinking about it and working on it. Therefore, it should be interesting and engaging enough for you to motivate your continued work on this topic.

- Specific: not too broad and not too narrow

- Feasible to research within a given timeframe: Is it possible to answer the research question based on your time budget, data and additional resources.

How do you find a topic or develop a feasible research idea in the first place? Finding an idea is not difficult, the critical part is to find a good idea. How do you do that? There is no one specific way how one gets an idea, rather there is a myriad of ways how people come up with potential ideas (for example, as stated by Varian (2016)).

You can find inspiration by

- Looking at insights from the world around you: your own life and experiences, observe the behavior of people around you

- Talking to people around you, experts, other students, family members

- Talking to individuals outside your field (non-economists)

- Talking to professionals working in the area you are interested in (you may use social media and professional platforms like LinkedIN or Twitter to make contact)

- Reading journal articles from other non-economic social sciences and the medical literature

- Reading economic and non-economic newspapers and magazine articles (e.g., Süddeutsche, Frankfurter Allgemeine, Tagesspiegel, The Economist, the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Guardian), watching TV programs

- What are the issues being discussed?

- How do these issues affect people’s lives?

In addition you could

- Go to virtual and in-person seminars, for example, the Essen Health Economics Seminar

- Look at abstracts of scientific articles and working papers

- Look at the literature in a specific field you are interested in, for example, screening complete issues of journals or editorials about certain research advancements. By reading this literature you might come up with the idea on how to extend and refine previous research.

Once you identified a research question that is of interest to you, you need to define a hypothesis.

2.2 What is a hypothesis?

A hypothesis is a statement that introduces your research question and suggests the results you might find. It is an educated guess. You start by posing an economic question and formulate a hypothesis about this question. Then you test it with your data and empirical analysis and either accept or reject the hypothesis. It constitutes the main basis of your scientific investigation and you should be careful when creating it.

2.2.1 Develop a hypothesis

Before you formulate your hypothesis, read up on the topic of interest. This should provide you with sufficient information to narrow down your research question. Once you find your question you need to develop a hypothesis, which contains a statement of your expectations regarding your research question’s results. You propose to prove your hypothesis with your research by testing the relationship between two variables of interest. Thus, a hypothesis should be testable with the data at hand. There are two types of hypotheses: alternative or null. Null states that there is no effect. Alternative states that there is an effect.

There is an alternative view on this that suggests one should not look at the literature too early on in the idea-generating process to not be influenced and shaped by someone else’s ideas (Varian 2016). According to this view you can spend some time (i.e. a few weeks) trying to develop your own original idea. Even if you end up with an idea that has already been pursued by someone else, this will still provide you with good practice in developing publishable ideas. After you have developed an idea and made sure that it was not yet investigated in the literature, you can start conducting a systematic literature review. By doing this, you can find some other interesting insights from the work of others that you can synthesize in your own work to produce something novel and original.

2.2.2 Identify relevant literature

For your research project you will need to identify and collect previous relevant literature. It should involve a thorough search of the keywords in relevant databases and journals. Place emphasis on articles from high-ranking journals with significant numbers of citations. This will give you an indication of the most influential and important work in the field. Once you identify and collect the relevant literature for your topic, you will need to critically synthesize it in your literature review.

When you perform your literature review, consider theories that may inform your research question. For example, when studying physician behavior you may consider principal-agent theory.

2.2.3 Research question or literature review: the chicken or the egg problem?

Whether you start reading the literature first or by developing an idea may depend on your level (graduate student, early career researcher) and other goals. However, thinking freely about what you like to investigate first may help to critically develop a feasible and interesting research question.

We highlight an example how to start with investigating the real world and subsequently posing a research question (“How to Write a Strong Hypothesis Steps and Examples” 2019; “Developing Strong Research Questions Criteria and Examples” 2019; Schilbach 2019). For example, based on your observation you notice that people spend extensive amount of time looking at their smartphones. Maybe even you yourself engage in the same behavior. In addition, you read a BBC News article Social media damages teenagers’ mental health, report says.

(#fig:social_media)Social media and mental health

Source: BBC

You decide to translate this article and your observations into a research question: How does social media use affect mental health? Before you formulate your hypothesis, read up on the topic of interest. Read economic, medical and other social science literature on the topic. There is likely to be a vast amount of literature from non-economic fields that are doing research on your topic of interest, for example, psychology or neuroscience. Familiarize yourself with it and master it. Do not get distracted by different scientific methodologies and techniques that might seem not up-to-par to the economic studies (small sample sizes, endogeneity, uncovering association rather than causation, etc.), but rather focus on suggestions of potential mechanisms.

A hypothesis is then your research question distilled into a one sentence statement, which presents your expectations regarding the results. You propose to prove your hypothesis by testing the relationship between two variables of interest with the data at hand. There are two types of hypotheses: alternative or null. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. The alternative hypothesis states that there is an effect.

A hypothesis related to the above-stated research question could be: The increased use of social media among teenagers leads to (is associated with) worse mental health outcomes, i.e. increased incidence of depression, eating disorders, worse well-being and lower self-esteem. It suggests a direction of a relationship that you expect to find that is guided by your observations and existing evidence. It is testable with scientific research methods by using statistical analysis of the relevant data.

Your hypothesis suggests a relationship between two variables: social media use (your independent variable \(X\)) and mental health (dependent variable \(Y\)). It could be framed in terms of correlation (is associated with) or causation (leads to). This should be reflected in the choice of scientific investigation you decide to undertake.

The null hypothesis is: There is no relationship between social media use among teenagers and their mental health.

2.3 Resources box

2.3.1 How to develop strong research questions

- The form of the research process

- Varian, H. R. (2016). How to build an economic model in your spare time. The American Economist, 61(1), 81-90.

2.3.2 Identify relevant literature from major general interest and field literature

To identify the relevant literature you can

- use academic search engines such as Google Scholar, Web of Science, EconLit, PubMed.

- search working paper series such as the National Bureau of Economic Research, NetEc or IZA

- search more general resource sites such as Resources for Economists

- go to the library/use library database

2.3.3 Assess the quality of a journal article

Several rankings may help to assess the quality of research you consider

- Journals of general interest and by field in economics and management - For German-speaking countries, consider the VWL / BWL Handelsblatt Ranking for economics and management - The German Association of Management Scholars provides an expert-based ranking VHB JourQual 3.0, Teilranking Management im Gesundheitswesen - Web of Science Impact Factors - Scimago

- Health Economics, Health Services and Health Care Managment Research: Health Economics Journals List

- Be aware that like in any other domain there are predatory publishing practices.

Use tools to investigate how a journal article is connected to other works

- Citationgecko

- Connected papers

- scite_ – a tool to get a first impression whether a study is disputed or academic consensus

2.4 Checklist to get started with formulating your hypothesis

- Find an interesting and relevant research topic, if not assigned

- Try to suck up all information you can easily obtain from various sources within and outside academic literature

- Formulate one compelling research question

- Find the best available empirical and theoretical evidence that is related to your research question

- Formulate a hypothesis

- Check whether data are available for analysis

- Challenge your idea with your fellows or senior researchers

2.5 Example: Hellerstein (1998)

As an illustration of the research process of formulating a hypothesis, designing a study, running a study, collecting and analyzing the data and, finally, reporting the study, we provide an example by replicating Judith K. Hellerstein’s paper “The Importance of the Physician in the Generic versus Trade-Name Prescription Decision” that was published in 1998 in the RAND Journal of Economics.

Hellerstein’s 1998 paper has impacted discussion about behavioral factors of physician decisions and pharmaceutical markets over two decades. The study received 448 citations on Google Scholar since 1998 by 27/03/2022, including recent mentions in top field journals such as Journal of Public Economics (2021), Journal of Health Economics (2019), and Health Economics (2019).

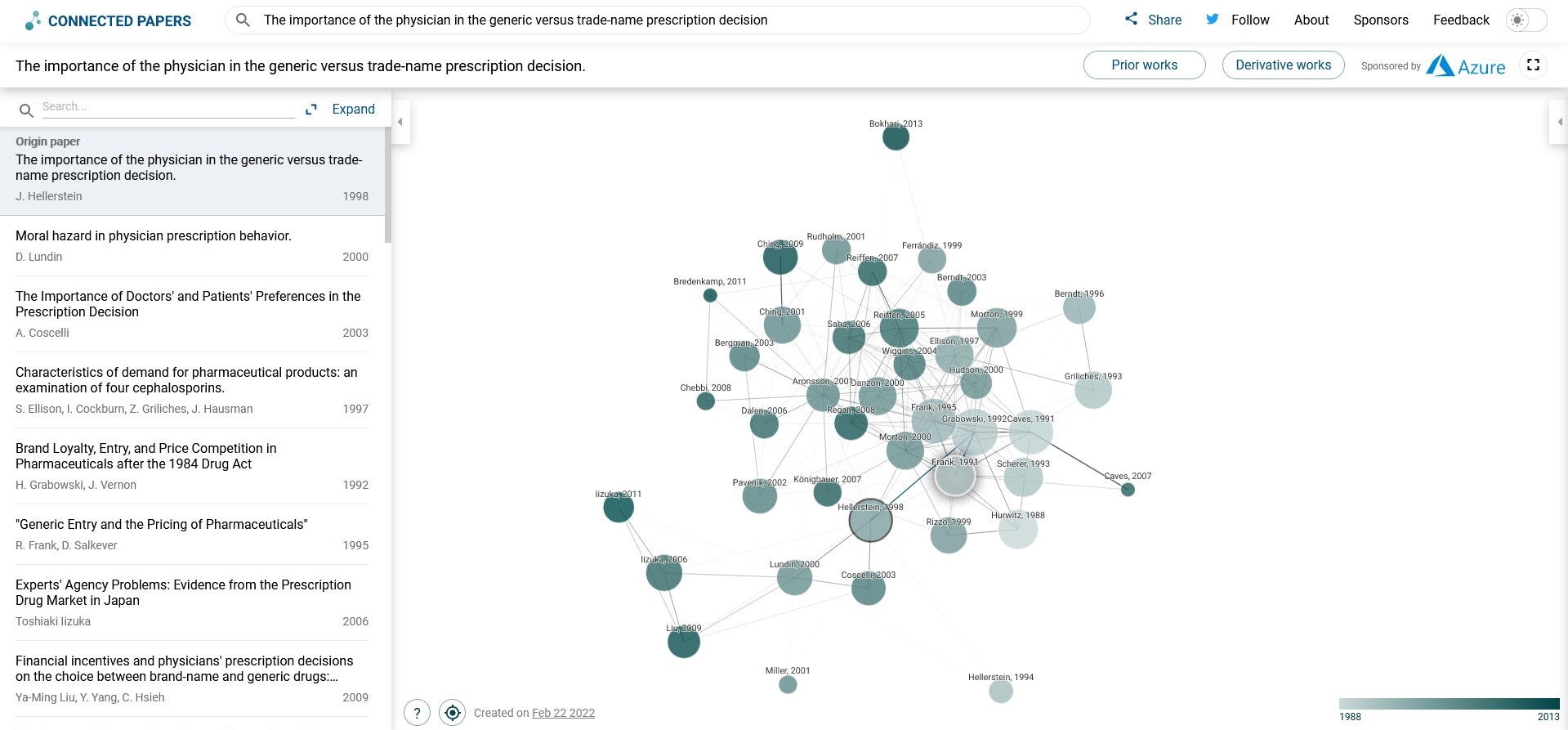

Figure 2.1: Connected graph of Hellerstein (1998), February 2022

Figure 2.1 shows a connected graph of prior and derivative works related to the study.

The work has impacted the literature researching the role of physician behavior and its influence on access, adoption and diffusion of health services, moral hazard and incentives in prescription and treatment decisions and the influence of different payment schemes, and a vast body of literature studying the pharmaceutical market.

The research that has been influenced by Hellerstein includes evidence on:

- generic drug entries and market efficiency

- the effectiveness of pharmaceutical promotion

- the effectiveness of price regulations

- the role of patents and dynamics of market segmentation

At the end of each chapter, we demonstrate insights into this study that we replicate.

2.5.1 Context of the study - escalating health expenditures

In the United States, the total prescription drug expenditure in 2020 marked about 358.7 billion US Dollars (Statista n.d.). The prescription of generic drugs in comparison to more expensive brand-name versions is an option in reducing the total health care expenditure. Generic drugs are bioequivalent in the active ingredients and can serve as a channel to contain prescription expenditure (Kesselheim 2008) as generic drugs are between 20 and 90% cheaper than their trade-name alternatives (Dunne et al. 2013).

2.5.2 Research question - How does a patient’s insurance status influence the physician’s choice between generic compared to brand-name drugs?

Physicians are faced with a multitude of medication options, including the choice between generic and trade-name drugs. Physicians ideally act as agents for their patients to identify the best available treatment option based on their needs. Choosing the best treatment entails cost of coordination and cognition. The prescription of generic drugs may serve as an example to what extent physicians customize treatments according to patients’ needs with regards to cost. From an economic point of view we may expect that once a generic drug is available, a perfectly rational agent (i.e. physician) would prescribe a generic drug instead of the trade-name version if therapeutically identical (Dranove 1989). This leads to the following research question: “Do physicians vary their prescription decisions on a patient-by-patient basis or do they systematically prescribe the same version, trade-name or generic, to all patients?”.

The 1998 Hellerstein’s study examines two hypotheses:

- The physician prescribing choice influences the selection of a generic over a brand-name drug

- The patient’s insurance status influences the physician’s choice between generic and brand-name drugs.

For the purpose of this example and in the replication exercise we focus on the second aspect.

2.5.3 Hypothesis

The paper formulates the following hypothesis:

Physicians are more likely to prescribe generics to patients who do not have insurance coverage for prescription pharmaceuticals (moral hazard in insurance)

Hellerstein (1998) discusses that, based on insurance status, some patients may demand certain care more than others. If, for example, the prescription drug is reimbursed by the patient’s health insurance, this may cause overconsumption. This behavior can potentially differ by the patient’s insurance scheme. A patient that has no insurance and, thus, does not get any reimbursement for prescription drugs, might have a higher incentive to demand cheaper generic drugs (Danzon and Furukawa 2011) than a patient with insurance that covers prescription drugs, either generic or trade-name. Given that the United States have different insurance schemes with varying prescription drug coverage, it is of interest to investigate the role of a patient’s insurance status in the physician’s choice between generic compared to brand-name drugs.

Hellerstein (1998) considers a patient’s insurance status as a matter of dividing the study population in groups for which the choice between generic and brand-name drugs differs. She suggests that There is a relationship between the prescription of a generic drug and insurance status of a patient. (Hellerstein 1998).

Providing answers to a research question requires formulating and testing a hypothesis. Based on logic, theory or previous research, a hypothesis proposes an expected relationship within the given data. According to her research question, Hellerstein hypothesizes that: Physicians are more likely to prescribe generics to patients who do not have insurance coverage for prescription pharmaceuticals.

Specifically, she writes “if there is moral hazard in insurance when it comes to physician prescription behavior, there will be differences in the propensity of physicians to prescribe low-cost generic drugs, and these differences will be (partially) a function of the insurance held by the patient. In particular, if moral hazard exists, patients with extensive insurance coverage for prescription drugs (like those on Medicaid in 1989) should receive prescriptions written for generic drugs less frequently than patients with no prescription drug coverage.” (Hellerstein 1998, 113)

Based on Hellerstein’s considerations, we expect the effect of the insurance status on whether a patient receives a generic to be different from zero. To obtain a testable null hypothesis, we reformulate this relationship so that we reject the hypothesis if our expectations are correct. This means, if we expect to see an effect of insurance on prescriptions of generics, our null hypothesis is that insurance status has no effect on the outcome (prescription of generic drugs). No moral hazard arises from having obtained insurance.

References

Danzon, Patricia M., and Michael F. Furukawa. 2011. “Cross-National Evidence on Generic Pharmaceuticals: Pharmacy Vs. Physician-Driven Markets.” NBER Working Paper 17226, July, http://www.nber.org/papers/w17226. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17226.

Dranove, David. 1989. “Medicaid Drug Formulary Restrictions.” The Journal of Law and Economics 32 (1): 143–62. https://doi.org/10.1086/467172.

Dunne, Suzanne, Bill Shannon, Colum Dunne, and Walter Cullen. 2013. “A Review of the Differences and Similarities Between Generic Drugs and Their Originator Counterparts, Including Economic Benefits Associated with Usage of Generic Medicines, Using Ireland as a Case Study.” BMC Pharmacology & Toxicology 14 (January): 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-6511-14-1.

Hellerstein, Judith K. 1998. “The Importance of the Physician in the Generic Versus Trade-Name Prescription Decision.” The RAND Journal of Economics 29 (1): 108–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/2555818.

Kesselheim, Aaron S. 2008. “Clinical Equivalence of Generic and Brand-Name Drugs Used in Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” JAMA 300 (21): 2514. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2008.758.

Pischke, Steve. 2012. “How to Get Started on Research in Economics?” http://econ.lse.ac.uk/staff/spischke/phds/get_started.pdf.

Schilbach, Frank. 2019. “5 Steps Toward a Paper.” MIT 14.192 guest lecture. https://www.dropbox.com/s/q7wjaidl5w91srt/Guest%20lecture%20FS.pdf?dl=0.

Statista. n.d. “Prescription Drug Spending in U.S. 1960-2020.” Statista. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/184914/prescription-drug-expenditures-in-the-us-since-1960/.

Varian, Hal R. 2016. “How to Build an Economic Model in Your Spare Time.” The American Economist 61 (1): 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0569434515627089.